Are day sales still a reliable indicator of the art market’s health?

Statistics suggest that the humble day sale is becoming almost as highly choreographed as the blue-chip evening auctions. By Susan Moore

Confidence is key in the art market. For buyers to continue to participate in this most opaque of marketplaces, it must be seen to prosper. Given that the only accurate statistics reflecting the health of its various constituent parts are provided by public auctions, their results matter. It is almost irrelevant that far more important private transactions may be taking place in dealer’s galleries, at art fairs or even in the auction houses themselves.

With the increasingly curated blue-chip auctions of Impressionist and modern, post-war and contemporary art, third-party guarantees make the picture more complicated. (According to a recent report by ArtTactic, since 2017 between 40% and 60% by value and 20% to 30% by volume of evening sale lots at Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips have been guaranteed to sell. And 2022 is forecast to set a new record in the value and number of guarantees.) The humble day sale has therefore come to be seen as a bellwether, a more reliable indicator of what was really happening in the market. But is this really the case? In light of recent statistics, it might be time to reconsider the day sale – as well as mid-season sales and the explosion of online selling platforms processing and promoting lower-value works of art.

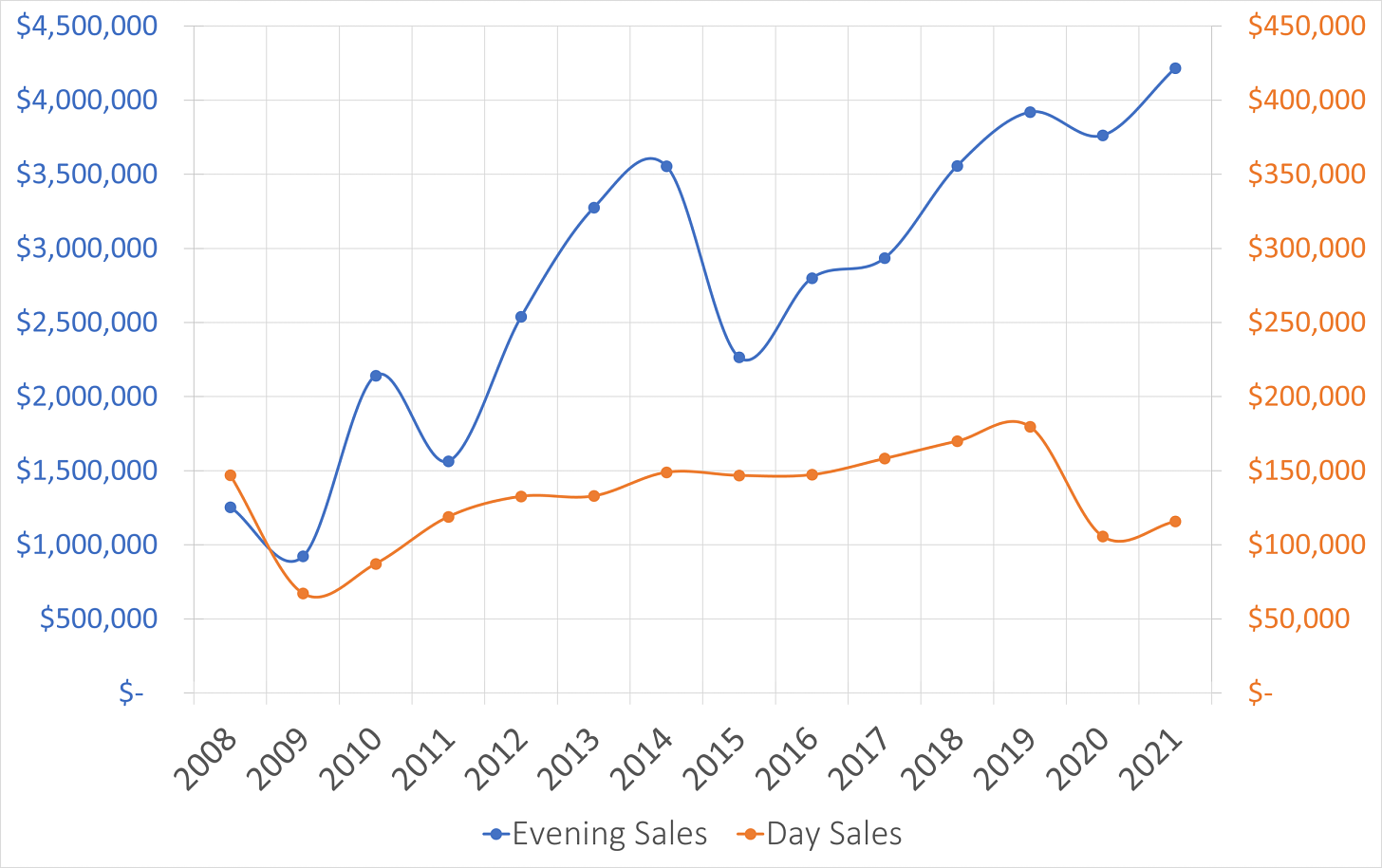

On first look, it is true that the average lot value for day sales has remained relatively consistent – particularly in comparison to the famously orchestrated evening sales. Given the catastrophic financial risks of failure to sell a top lot, it is hardly a shock to find that the average lot value for the New York fall evening auctions of post-war and contemporary art at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips has soared over the last 13 years. From just over $1m in 2008, the amount has risen and fallen in at times dramatic peaks and troughs to over $4m in 2021. In contrast to that mountainous ascent, where the mean value has risen by over 200 per cent, the day sale figures have remained more or less the same. The mean line here represents a gentle upward incline of around 36 per cent, beginning and ending in the foothills around $100,000, although individual prices have not infrequently passed $1m.

The relatively consistent day sale figures reflect not only the increasing polarity between the best and rest but also suggest lower prices embedded within the wide range of material coming to these auctions. ‘As the second tier struggled, [those] prices have been adjusted,’ observes seasoned art adviser Nick Maclean. A plausible second reason for the modest increase in day sale values is that the major auction houses are concentrating on high-profile names and the top end of the market. An increasing amount of good material that would otherwise be consigned to bread-and-butter day sales in London, New York or Paris is now being consigned to ambitious and efficient regional auctioneers. Ketterer Kunst in Münich, for instance, has become one of the most important salerooms in this category in Europe.

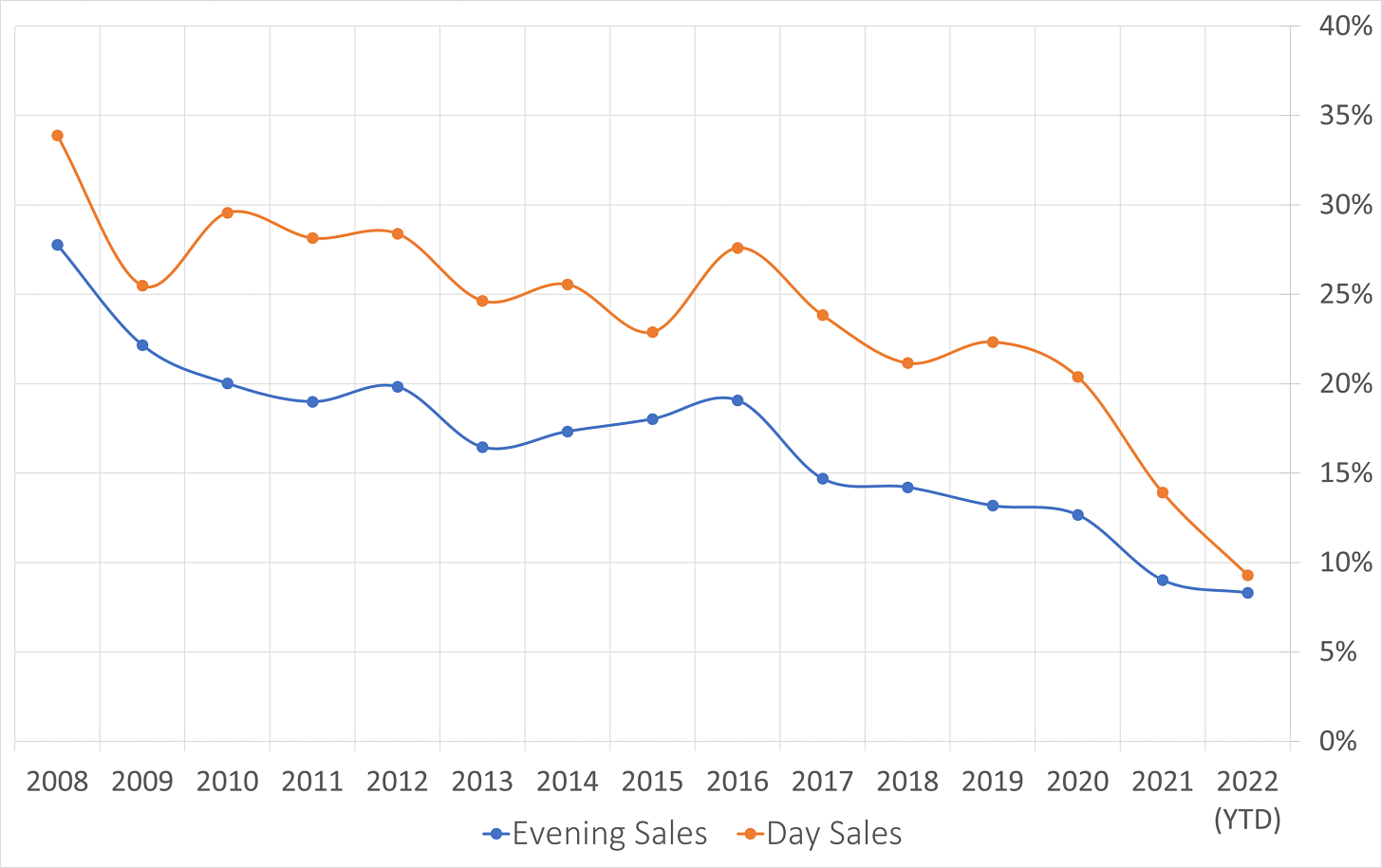

Perhaps more striking is that the number of unsold works of art has dropped for both the day and the evening sales for all post-war and contemporary auctions. Over the same period, the bought-in percentages of both fell from around an average of 30% to below 10% for the evening sales and just below 15% for the day sales. Both fell sharply after 2020. (The number of lots offered remained more or less stable – around 2,000 in evening auctions, and 5,000–6,000 in day sales). Like their evening counterparts, it appears that day sales are becoming increasingly choreographed.

‘If sell-through rates are improving, three things must be happening,’ says Matthew Stephenson, a former Christie’s director and now art adviser. ‘There must be better filtering of material, more effective means of reaching audiences, and realistic pricing. Buyers have access to more information than ever before, and the market will not tolerate over-estimating.’ Like Maclean, he believes that auction houses have become more selective in what they take for these sales and pragmatic about value. Perhaps most crucially, they have also been adept at harnessing technology to create competition online, benefiting from the ease and familiarity with which the world came to spend increasingly larger sums online during the pandemic, and massively expanding the global breadth and depth of the market. Their success has been predicated on what he describes as the ‘enormous confidence in the big brands’.

‘The digital revolution in the auction house is really what has driven the change in the data,’ confirms Sotheby’s Holly Braine. ‘We have been trialling strategies to engage maximum bidding interest and the make-up of our sales has changed considerably.’ In a bid to ‘cross-contaminate’ buyers, the two major day sales a year of Impressionist and modern art and contemporary art in London and New York were fused last year, with the usual 300 or so lots each pared back to around 100 to avoid buyer fatigue. As a result, sales have inevitably become more selective, with occasional high-value – even guaranteed – lots straying over from the evening sales and outperforming expectations as well as focusing the interest of those who would not normally look at the day offering.

Online sales have absorbed the residue – and generated more besides. ‘The flexibility of these online platforms has enabled us to be nimble in responding to current demand, and to accept a broader range of work as well as work at a much lower value than before,’ says Braine. ‘The sell-through rates for online sales are high, and we have accessed a far, far wider range of buyers and much younger buyers.’ Success has, she says, taken a huge amount of work, not least from enhanced online lot content and a dedicated marketing team that has hugely expanded over the last couple of years.

‘Having a successful day sale with strong results does give confidence in the market,’ agrees Anna Touzin of Christie’s. ‘We curate our sales as much as we can in the short window of our lead times: we think about what people are interested in and what will do well and invite owners to consign, trying to create groups.’ She adds: ‘What everyone wants to buy at the moment is emerging contemporary art.’

‘Demand for contemporary art is booming, and huge,’ confirms Rebekah Bowling of Phillips. ‘This is why we have seen our 20th-century and contemporary day sales and mid-season sales grow so much over the last few years,’ Between the fall sales of 2020 and 2021, 38% of day sale lots sold above their high estimates, often in multiples of their pre-sale estimates. Meanwhile, the auction house’s cutting-edge New Now sale in New York last month saw participation from 55 countries, and found record prices for some 14 mostly emerging artists. Says Bowling, ‘Five or six years ago, an artist entering the auction market might continue to outperform their estimates for a year or two but then you would see a tapering off in prices as demand was fulfilled. Over the last three years, a hot artist comes to the market and the prices just keep on getting bigger and bigger.’

Phillips is far from alone in moving aggressively into the territory of the primary art market, or in numbering speculative buyers among its clients. What is disappointing to note is how the risk-and-reward speculation that has long flourished among the trophy hunting ‘flippers’ operating in the elevated heights of the evening sales has taken root in the plains below. To the traditional auction drivers of death, debt and divorce, one might now add another: desire to make money.

Susan Moore is associate editor of Apollo.