The curious gulf between biennial stardom and auction success

Top biennials are seen as a reliable way for collectors to discover the best emerging artists. Just don’t expect headline-grabbing auction prices.

After two years of pandemic disruption, when NFTs and record sales for young figurative painters dominated the art world headlines, biennials are back. The Venice and Whitney Museum events opened in April to great acclaim, and more than two dozen are scheduled to open before the end of the year.

Although biennials are non-selling events, they present an opportunity for collectors to discover emerging artists exploring today’s ideas. “Biennials, much more than art fairs, are crucial for giving lesser-known artists a stage and context to produce works that might set new standards in contemporary art,” says Christian Oxenius, acting head of research at the International Biennial Association.

It is no surprise then, that established collectors are often listed as patrons of biennials, much as they are for museums. Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 Venice Biennale exhibition has 26 foundations and collectors supporting it, including Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Maja Hoffmann and Bob Rennie, who have also looked at biennials in the past to help build their own public art foundations.

What is perhaps less obvious to newer collectors choosing to travel to biennials are the pros and cons of using them as a tool for building an art collection. What is the longer-term career trajectory of biennial artists? Are biennials the place to find the next “hot” artist? Is a strong biennial track record an indicator of longer-term success?

Super-beings

To try and answer this, Critical Edge did research looking at the networks of 3,400 curators across 127 biennials over a 31 year period (1990 to 2021-2), and showing who curated what and which artists were shown. The list of biennials was headed by Documenta and the Venice Biennale, with the Gwangju, Whitney and São Paulo biennials just behind.

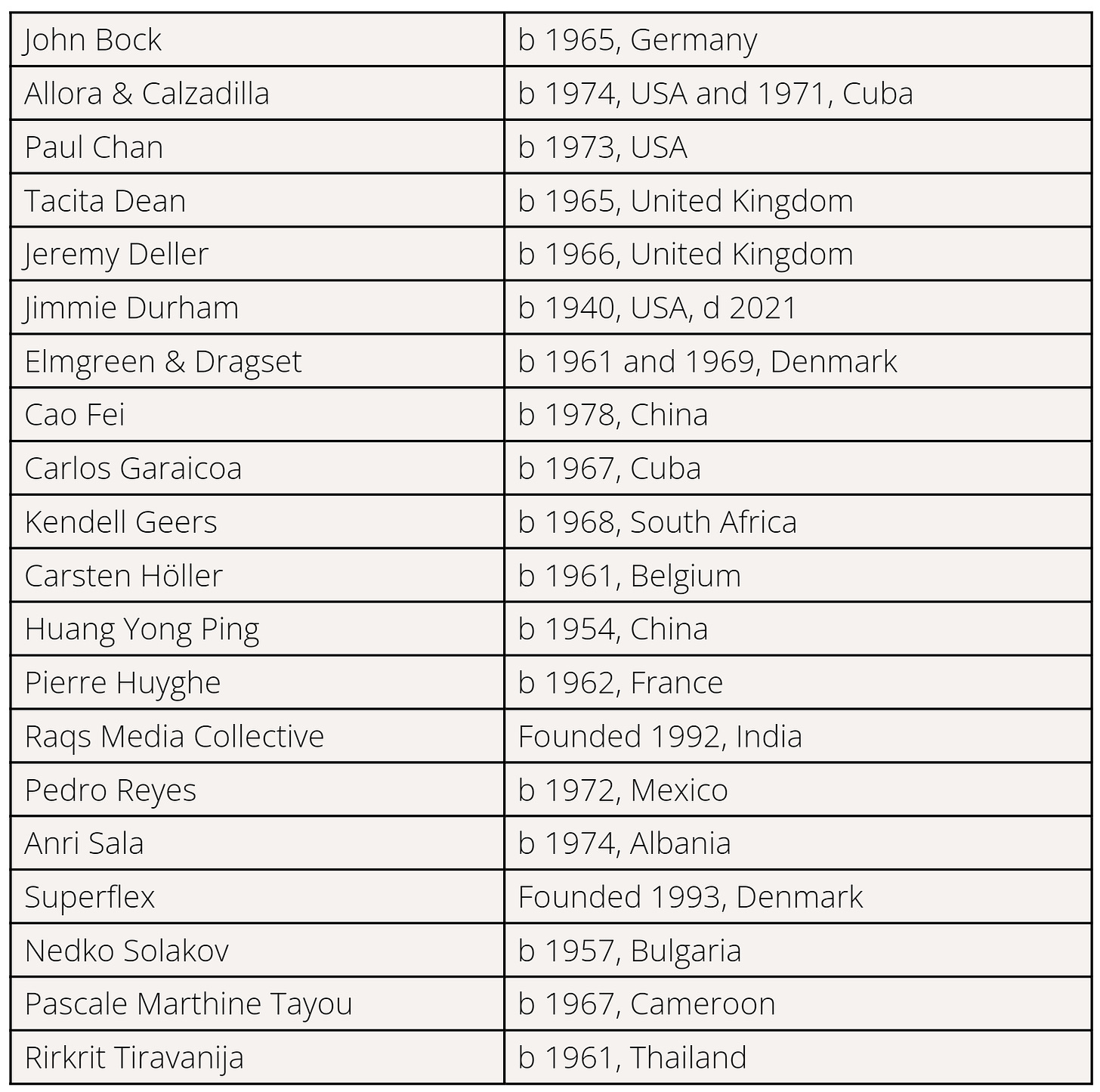

One of the many findings revealed by the data was the emergence of a highly visible group of 20 artists who, between 2000 and 2015, were chosen by a highly networked group of 15 curators. These artists were exhibited much more often than their peers - at between 8 and 14 biennials between 2000 and 2015.

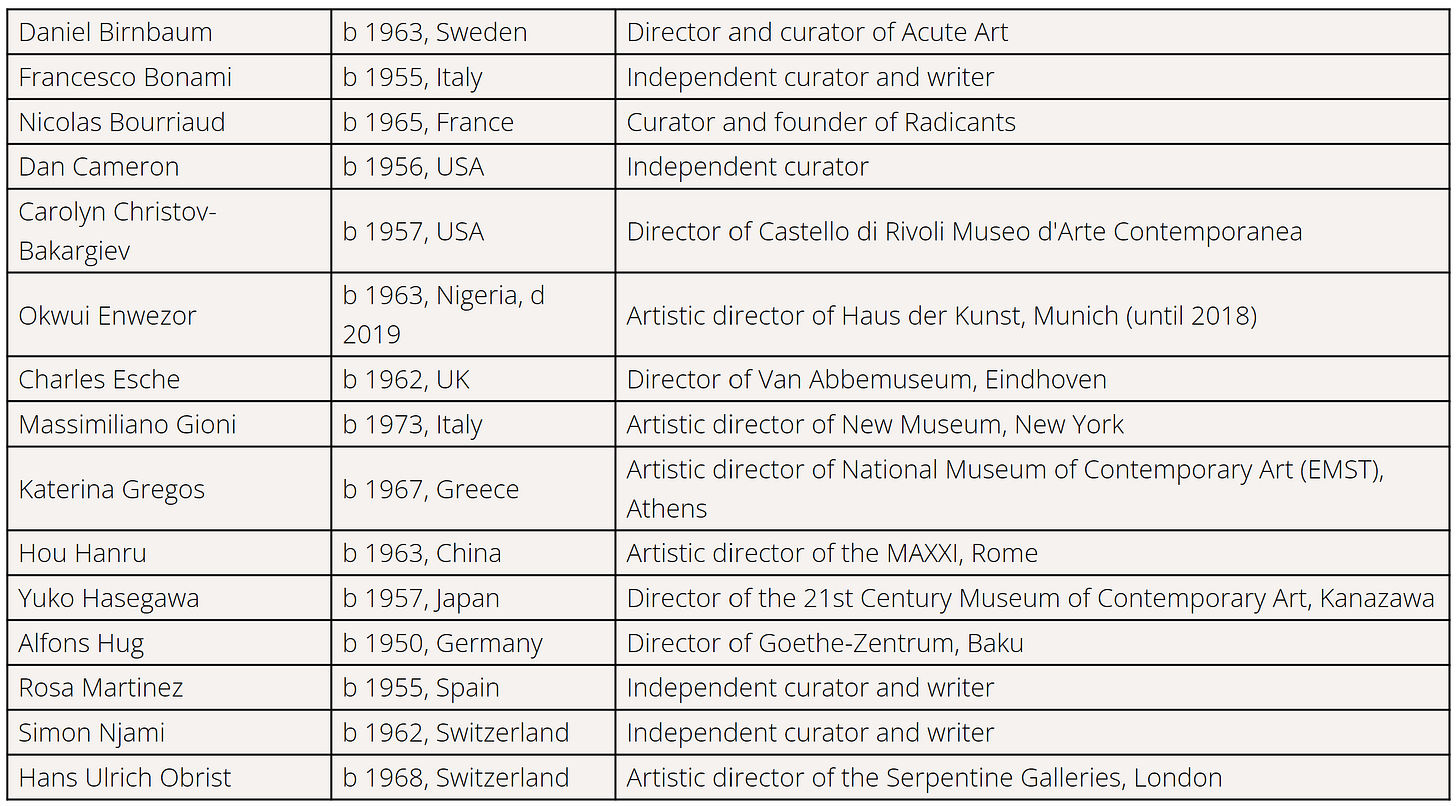

Moreover, the group of 15 so-called “super-curators” curated 20% of all the biennials researched during that period. Mostly born in the 1950s and 1960s, they include Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, Nicolas Bourriaud, co-founder of the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and the late Okwui Enwezor, artistic director of Munich's Haus der Kunst between 2011 and 2018, among others.

Although these super-curators showed a wide range of artists (more than 4,000 in total), the noticeable focus on the group of 20 “super-artists” could mean considering them among the best of the period. So how have their careers progressed as a result of this exposure?

Museums matter

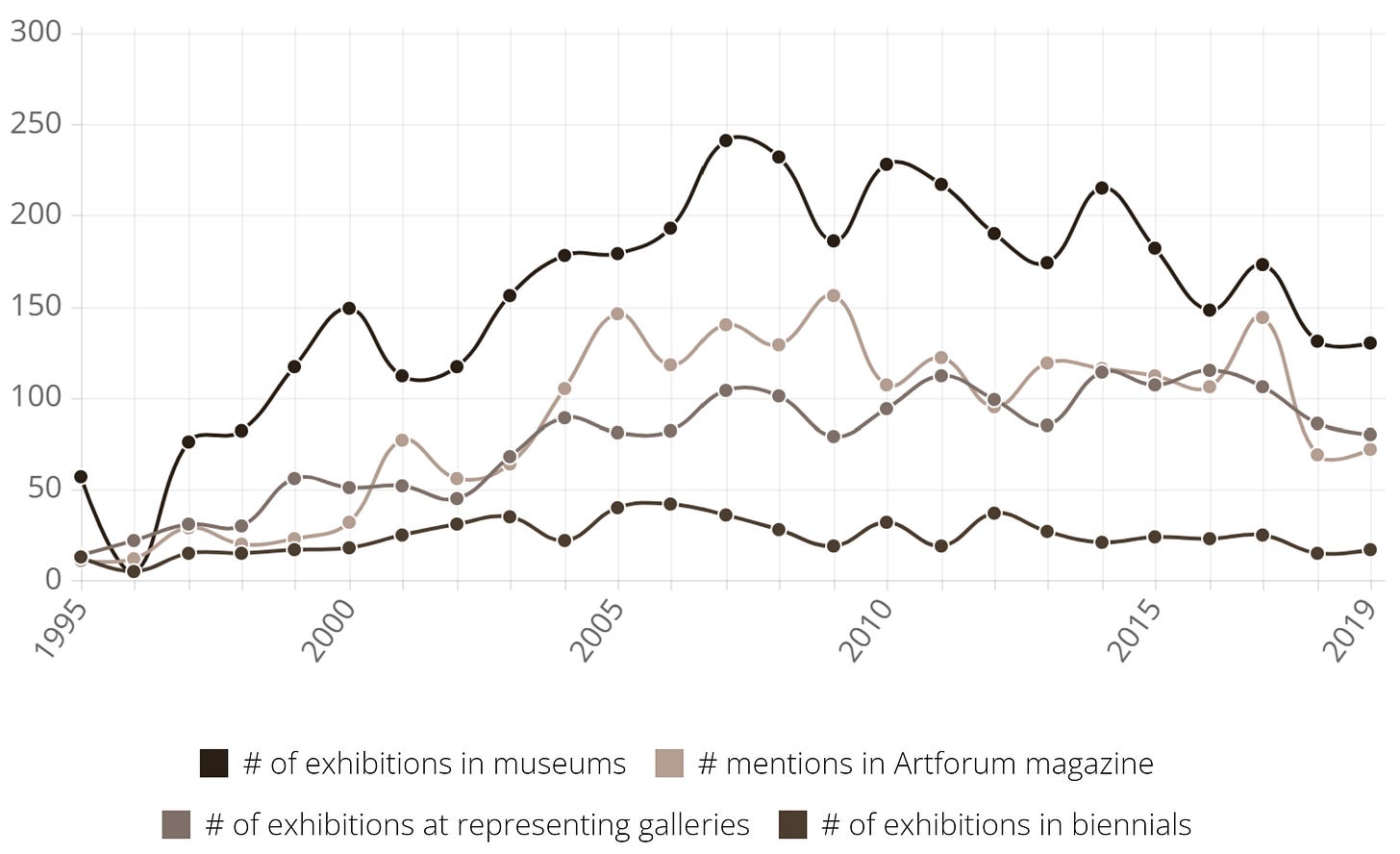

Like being chosen to exhibit at biennials, an artist’s institutional exhibition history reflects how curators and museum directors regard their work. For the 20 super-artists the numbers speak for themselves. Since 2000 their work has been shown in more than 6,500 exhibitions, averaging 12 group exhibitions and three solo shows a year, more than half in museums (the rest have been shows in commercial and non-commercial galleries, biennials and other venues). Nine have had solo exhibitions at the Tate, and seven at the Centre Pompidou. They have also been nominated or won more than 100 awards or prizes. Half have been nominated by the Guggenheim Museum in New York for the prestigious Hugo Boss Prize. Four have won. These artists were mostly in their 30s and 40s, often considered the prime years for artistic creativity.

But all this hasn’t stopped them from being susceptible to changing fashions. As the following graphs show, between 2015 and 2019 total worldwide exhibitions for the super-artists fell to their lowest level since 2002. So did biennial appearances and the frequency of coverage by influential publications such as Artforum.

Our research explains this shift as well. A new generation of curators, born in the late 1970s and 1980s, began to take over as the creative voices in biennials from 2015. They include Defne Ayas (born 1976), who co-directed the 2020 Gwangju Biennale with Natasha Ginwala; Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung (born 1977), the new director of Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, and Chus Martínez, director of the FNHW Academy of Art and Design in Basel. As they emerged, the number of biennials directed by the first generation of super-curators reduced by half, from six a year on average before 2015, to three a year afterwards.

And yet the frequent biennial presence and curatorial support for the super-artists does appear to guarantee longevity. Their work is in 280 public collections around the world, including major taste-making institutions. Fifteen of the 20 artists are in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection in New York.

Market forces

Olav Velthius, a professor of sociology at the University of Amsterdam, says that the art market “looks at signals of quality. For instance, what an important curator is saying about an artist; if the artist has exhibitions in museums; if influential collectors are buying their work.”

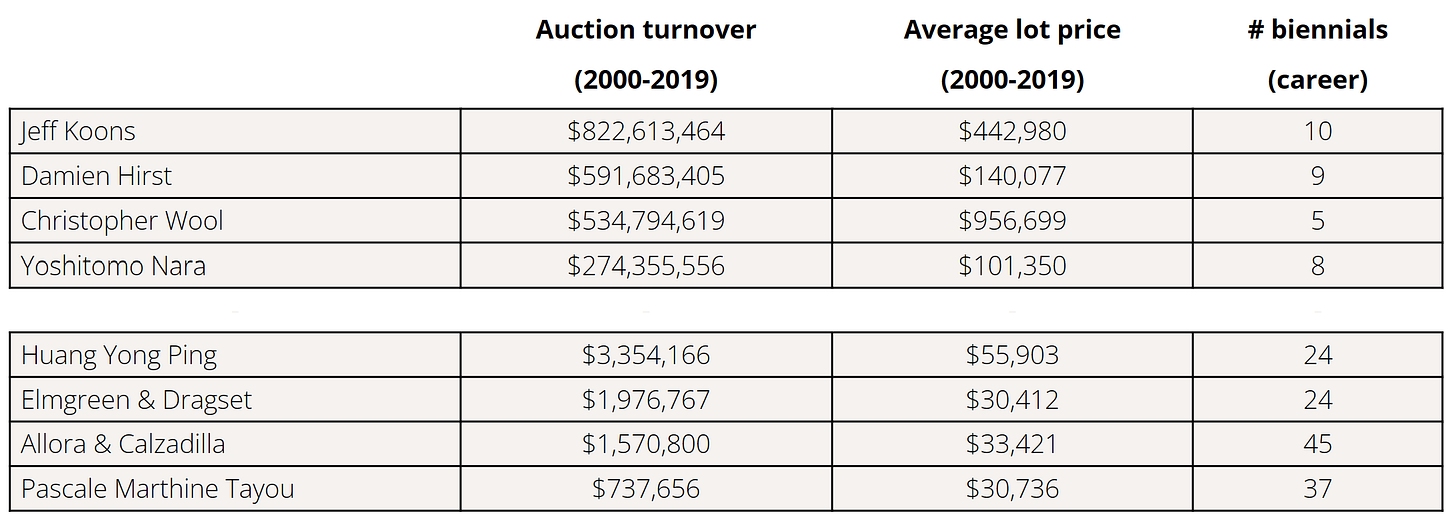

By his reckoning, the super-artists should perform well in the auction market, so it is surprising that they do not. In 2020, auction price database ArtPrice compiled a ranking of the top 1,000 contemporary artists by total auction turnover from 2000 to 2019. Only one of the super-artists, Huang Yong Ping, appears on the list, with a total auction turnover (including premiums) of $4.1m, less than 1% of those at the top of the table (headed by Jeff Koons, with a massive total auction turnover of almost $940m).

Not only do few works by the super-artists come to market, when they do, they seldom perform well. Year after year, most works that have come to auction have either not sold or sold for below their pre-sale estimates.

And yet, as a group, the super-artists are represented by 32 of the world’s leading international commercial galleries such as the Lisson Gallery, Pace and Victoria Miro. Their works are still taken to major art fairs such as Art Basel and Frieze and often sell, according to their galleries and press reports. Galerie Chantal Crousel sold a work from After UUmwelt, 2021, by Pierre Huyghe at FIAC in October 2021 to an Asian collection for €275,000. Kamel Mennour, meanwhile, is presenting Huang Yong Ping’s large sculpture American Kitchen and Chinese Cockroaches, 2019, at Art Basel’s Unlimited section in June, an expensive undertaking that implies confidence

Labour of love

The failure of the auction market to ‘recognise’ these artists could be a result of a number of factors. Almost none of the super-artists work in the more buyer-friendly medium of painting. Instead, their works are often installations, video works, prints, or sculptures. But another, altogether more subtle reason may be that the collectors buying these artists, presumably combined with careful placement by the dealers, have a different perspective on collecting, and are less inclined to sell, at least at auction.

Kamel Mennour gallery says that it is “often well-established collectors with a wide knowledge of contemporary art and the market” who buy works by Huang. Stephen Friedman Gallery, which represents Kendell Geers, says that it is “more established collectors” who show interest in his work, priced at up to €250,000.

Thanks to the huge increase in online auctions since the pandemic it has never been easier for new collectors to start buying art, but biennials demand more effort. And while finding new works at biennials may not lead to short-term returns in the auction market, the experience can be more fruitful.

“Do I believe that buying based on biennials is a good financial investment? No,” says Alain Servais, a well-known Brussels-based collector. He says he is in the final stages of acquiring works by four or five artists exhibited in this year's Venice Biennale. “If you want to measure the quality of your collection by commercial performance, with a five- or ten-year perspective, look at the artists that sell well at auction. I buy with a 30-year horizon. That has nothing to do with the market. It’s art history.”

Methodology

How we used our data

We mapped 127 of the top contemporary art biennials* from 1990 to the present day (2021-2) along with approximately 3,220 curators who worked on them

We weighted every biennial based on the frequency, variety, and relative importance

We created an iteratively ranked data set that revealed the influential networks of biennial curators

We then looked at which artists the curators chose for their biennials

*Our research focused on contemporary art biennials directed by professional curators showing artists of an international standard. We excluded specialist architecture, theatre, local and purely marketing events from our list of more than 300 biennials, to focus on 127 national and international-level exhibitions